|

By Dave Kim Minter greets me at her Soho loft one summer afternoon, and as humid and scene-y as it is outside she is perspiration-free and non-coutured. Not to say that she isn’t concerned with appearance. I’m handed a glass of water and told to wait while she puts on her signature fiery lipstick in the back room. She’s about to be photographed, after all. Covering her studio walls are massive paintings-in-progress and photo printouts, all of them slick and shiny under the warm studio lights. Most of the photographs are from her recent shoot with Pam Anderson: the men’s-mag goddess herself in soapsuds and bubble-gum pink lipstick, looking childlike, scared even, and very much not |

like the over-sexed Pam we’ve come to expect. Minter has rendered her almost unrecognizable save the barbed-wire tattoo. In one of the prints the glitter-dusted actress looks either dead or deep in meditation, embalmed in a luminous liquid. Born in Shreveport, Louisiana and raised in Florida, for Minter there was no idyllic childhood: Dad was an alcoholic, compulsive gambler, and occasional boxing promoter; Mom, a drug addict. Minter’s heroes were fashion models and “women with jobs,” who, in her 1950’s southern world, only existed in comic books and magazines. |

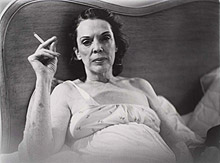

Art, Minter claims, was the only thing she was good at, being that most of her childhood was spent sketching glamour girls in the margins of her textbooks. She learned how to draw by drawing comic-strip heroine Brenda Starr, “a girl reporter with a twinkle in her eye,” who remains in syndication even today as a nostalgically beautiful gumshoe straight out of a Howard Hawks’ flick. Things at home weren’t as pretty. Over a weekend in 1969, while an undergraduate at the University of Florida, Minter snapped some pictures of her drug-addicted mother for a photography course (not taught by Diane Arbus, as legend and misreporting has it. Arbus, a visiting instructor at the time, though never Minter’s professor, saw the proof sheet and proclaimed it to be the only student work she gave a damn about that year.) and so mortified her classmates |

with the end results that she didn’t show them again for nearly thirty years. Honora Elizabeth Laskey Minter looks like a ghost in these grainy black and white prints, her hair in curlers or slick with fresh dye, chinning up in standard glamour poses but coming off as jaded, intimidating, and chillingly spectral. Minter’s mother wore wigs because she compulsively tore out her hair, and, as high as she was on various pills, put on makeup everyday whether she went out or not.

|

Bruce Hainley put it best in a 1992 Artforum piece, referring to her eyebrows as “freshly inked fermatas” and noting that “the esthetic of wig governs everything, suggesting that beauty, like existence, is artificial, askew, and concealing.” Minter moved to New York City in 1978, after finishing an MFA at Syracuse, and promptly entered what she calls a “coma”: nights touring the clubs of late 70’s-early 80’s downtown Manhattan, marathon boozing, and narcotic picnics back in an era when blow wasn’t supposed to be addictive. It was the perfect time to have a job teaching in a Catholic boy’s school, where she would chug Cokes and catch up on sleep in the minutes between classes. She’d been getting wasted since childhood, “on anything I could get my hands on,” and finally discovered in 1985 that the drugs had stopped working. Minter began the long, torturous task of cleaning up, ending a classic addiction narrative |

that she doesn’t find hip or romantic in the slightest. “It’s such a cliché,” she chides. “Everyone seems to think that drugs and alcohol give you a kind of freedom in making art, like it’s a path that’ll open up experience. But eventually you don’t get high anymore, you just get stupid.” Marilyn Minter is now expounding on the merits of freckles, pointing at an unfinished painting the size of a small billboard of a woman’s dappled face—another extreme close-up. Each freckle stands out clearly against the model’s pale skin. They’ve got crisp outlines, like land masses on a map or bits of bark left on a stripped tree. Having worked a little in fashion, the artist hates the fact that freckles are constantly removed or retouched in commercial photographs. They are not flaws, she insists. Neither are pimples, stray hairs, birthmarks, wrinkles, or age spots, though, |

when the photographer for this publication shows up, Minter jibes: “Make me look young and thin.” |

I’m still not sure if she loves the glamour industry, hates it, enjoys it with some critical distance, likes parodying it to the point where she’s better at it than they are, or skips mirthfully among different convictions. She is showing me a fancy cocktail dress acquired from a recent fashion shoot. It is black, delicately springy, and unimaginably expensive. She doesn’t care for it much, at least not for her own wardrobe, preferring less theoretical attire for social outings. I ask her what she does with the expensive shoes, accessories, and assorted goodies she gets gratis from her freelance photography gigs. “I give them away as Christmas presents,” she says. “I only do commercial work so I can use the outtakes.” One reason why Minter doesn’t do much fashion photography is that she rarely agrees with the editors on which prints are worth publishing. |

The artist is drawn to imperfection, stuff that no one’s supposed to see: underarm stubble, loose skin accordioned at the ankles, dirt. In March 2006, Minter’s and the public arts organization Creative Time took out ad space on four billboards in Manhattan’s Chelsea district. Replacing consumer product advertisements and a billing for North Country (Charlize Theron’s last uglification movie) were four massive photographs resembling ads for fancy high heels. With titles like Splish Splash, Shit-Kicker, and Mudbath, they were anything but; Minter had her models kick around three different pairs of gemmed shoes in dirty water while she photographed. The mud-spattered results stayed up in Chelsea the entire month. Soiled couture on New York City billboards…what did it mean? Was Minter exposing the baseness of high-fashion advertising? Was this her tell-off to consumerism, a caveat for the wanna-be chíc? |

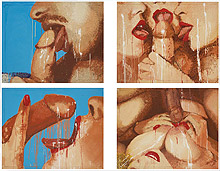

“I don’t pass any moral judgment,” she says, waving away my questions. “Who am I to tell people what to do? I love the idea of making a startling image just for fun.” In 1989, after experimenting with dot screens and Pop Art, Minter felt compelled to do something completely new. “I thought, ‘I know—I’ll do pornography. I’ll do hardcore pornography!” If other women artists were exploring the erotics of objects, the erotics of consumption, |

then why not investigate the erotic itself? Scouring New York’s sex shops and adult bookstores for inspiration, Minter carefully selected and painted a series of close-ups that were compelling or funny to her. Three women croon over an erect penis in one painting titled The Supremes, which, with the exception of the solid white streaks projecting from the “microphone” onto willing fingers and tongues, is painted in seedy benday-dot fashion, as if seized from the back pages of a newsweekly, and presented on a bulky metal first-aid kit. “I did these cumshots and thought they were really funny. I thought, ‘What’s the big deal?’ but people went nuts. Everybody likes to look at porn. I mean, the Internet’s there because of pornography. Let’s get real.” Minter had no interest in the polite or tame. She zoomed in on blowjobs and masturbating women. |

She obscured faces, fragmented bodies, and made sexual anatomies seem like contraband, as if welcoming the charges of hegemony and objectification they would produce. Surely people would see the humor and irony behind them. Her timing couldn’t have been worse. Here was a woman artist painting porn (erect and sputtering cocks, no less) in the politically correct 80’s and early 90’s, when feminists from the left and right |

were teaming up against the porn industry. Twin storms Catherine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin had altered climates of “decency” across the country. Minter was excoriated by nearly all of the critics, who saw in her work unapologetic images of women as victims and objects. They accused her of ripping off male porn, tagged her a traitor to feminism, and nearly ran her out of town. “I was inconsolable,” she remembers. “Nobody could see my point of view. I thought, ‘Am I crazy? How come nobody else is seeing what I’m seeing?’” At Salon 94, Minter’s gallery on the Upper East Side, several of her pornographic, enamel-on-aluminum works from 1991 to 1994 remain in storage. They are unsold and shown only upon request. Upon close inspection of some, one will notice scrapes and runs in the paint, |

burns where Minter poured chemicals, and long, deliberate scores running the paintings’ length in the way a vandal might key a car. The artist recalls how she would feel so bad about getting bashed by the critics that she would, in turn, abuse her paintings—until they literally bled. Flipping through her recent monograph (Marilyn Minter, Gregory Miller & Co., 2007), she points out the ones that were hardest hit. “I would put acid on the surface, sand sections, and make ‘em bleed yellow paint. I would just kick the shit out of these paintings.” Minter’s 40-year career has only recently reached its zenith. After winning back the admiration of critics, the artist has had a solo exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and a much-envied spot in the |

2006 Whitney Biennial in which her work was the invitation image. In 2007, her first retrospective monograph was published by Gregory R. Miller & Co., and she had shows in Sweden, the U.K., Spain, and France. Her photos of Pam were commissioned by the art quarterly Parkett, later featured on the cover of Zoetrope: All-Story, which she guest-designed, and following that were used in paintings. So what does Marilyn Minter do for fun? “I play video games and read trash magazines.” In between sessions of playing Bejeweled on her Treo, she digests US Weekly and the New Yorker. She checks PerezHilton.com religiously. Her favorite leisure activity is reading biographies, “mostly of sybarites” like |

Edie Sedgwick and Nico, though the last one she read was on Diane Arbus. She is also the world’s biggest fan of HBO’s The Wire, and finds it shameful that I haven’t seen all four seasons. |

Lately, though, she hasn’t had much free time. Her phone interrupts us constantly during our interview. She discusses what she believes is a 20th century phenomenon: women artists coming to fame late in their careers, “post-menopause.” Whatever the reason, Minter isn’t complaining. Traveling back and forth between her Soho space and her home studio in upstate New York, the 60-year-old artist has no plans to slow down. She says it’s unlikely that she’ll take on more commercial work, at least any in which she’s not in control. “I see ads where the hair’s wet, the grass is wet, and the skin’s totally dry. It’s so totally contrived and phony-looking I can’t stand to look at it.” From portraits of addiction to porno to Dior heels, Minter’s paintings and photographs have embraced messiness, the accidental, sweat- and mud-covered |

moments when beauty is caught boiling in the sun or falling into a puddle. As slick and sensual as her work looks, there is always a blemish, something unmistakably human pushing through the veneer, democratizing the glamour. The artist’s philosophy is simple, summed up by her in an interview with artist Mary Heilmann. “If you’re dancing in a disco all night your feet get dirty,” she quips, “even if you have the most expensive shoes on.” |

||

©2006 Smyles & Fish